[From Illustrated Notes on Manks Antiquities, 1904]

The most notable ancient structures of the Historic Period are the Castles of Peel and Rushen. With respect to the former, which stands on St. Patrick's Isle, about 7½ acres in extent, we have already referred to the mound near the centre of the islet as having possibly been a stronghold since neolithic times. The first buildings of stone would probably be the originals of the Chapels of St. Patrick and St. German, and, next to these, perhaps, the Round Tower on the highest part of the Island. The upper part of the latter has apparently been rebuilt in mediaeval days, but it is likely that it was never much higher than now, resembling in this respect the Towers at Turlough and Dromiskin, in Louth. It is 50 feet high, the circumference at base is 45 feet. About 7 feet above the ground is a doorway looking eastwards (facing the entrance to St. Patrick's). The tower is built of sandstone regularly laid in courses, the wide jointings filled in with extremely hard shell mortar. Near the top are four square-headed apertures facing the cardinal points, and one other lower down on the N.W. or seaward side. It is, as now seen, more cylindrical than the Irish towers, but its design and use as belfry, and as keep in wbieh relics and valuables were deposited, and into which the ecclesiastics could retire for security, were no doubt suggested by these.

The Cathedral is cruciform, having a central tower, but without aisles or porches. Its internal length is 114ft. 6in., the width at the intersection of the transepts is 68ft. Sin. The height of the tower, including the square belfry turret, is 83ft., and of the choir wall 18ft. ; the thickness of the wall 8ft. The Rev. J. Quine thinks the Early English, Decorated, and Norman chancel was built during the Episcopate of Michael, about 1195, and that even then it may have been on an older foundation; but the tower, transepts, and nave were the work of Symon (about 1226), previously Abbot of Iona, which may partly account for the resemblance to Iona, and the position of the Bishop's Palace adjoining the Cathedral on the north. At a later date the so-called crypt was inserted under the chancel, the floor of which was raised nearly three feet. The north transept arch is Early Decorated, the southern and western arches are later work.

The fine embattled walls (four feet thick) surrounding the islet are said to have been erected by Henry, fourth Earl of Derby, in 1593. The approach has been ruined in appearance by modern quays and cement work, but one may still see some of the rude steps, cut in the solid rock, leading to the portcullis door of the old square tower, which is supposed to be early fourteenth century work.

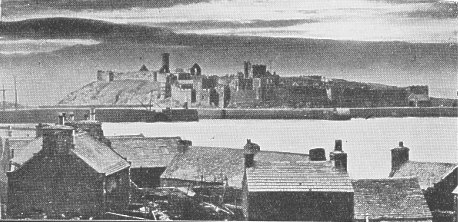

Godred II. died here in 1187, and King Olave also died at Peel, in 1237. We read of Reginald's descent upon it in 1228, when he burnt Olave's ships and those of all the chiefs of Man. It seems, therefore, that Olave must have had a stronghold here, though now no trace remains, unless the entrance tower is of that date. Our figure (fig. 42), giving a general view of the Castle with the Round Tower in the distance, is from a photograph by Mr. G. B. Cowen.

Fig. 42. View of Peel Castle on St. Patrick's Isle, from the town. Photo. by G. B. Cowen.

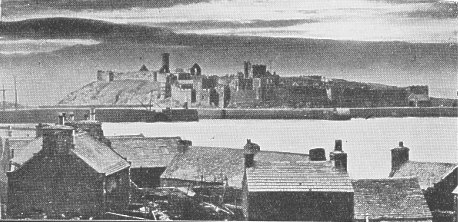

Rushen Abbey, on the Silverburn, in the village of Ballasalla and Parish of Malew, dates from the twelfth century, Ivo, Abbot of Furness, having in 1134 received a grant of lands for the purpose from King Olave. Cumming thinks there may have been some sort of a religious house earlier, though there is no notice of buildings in the Chronicon Manniae (kept by the Monks at the Abbey) till 1192, when it is recorded that the monks were transferred to Douglas for four years, during which they were engaged in enlarging the accommodation at Rushen. The Church was not completed and consecrated till 1257. According to Chaloner's drawings, made in the seventeenth century, there were five towers of rude masonry, with square-headed openings. The only decided architectural detail is a plainly chamfered arch in the Church tower, one apparently of an arcade running North from the tower, three others now in the Grammar School, which was the old Church of St. Mary; Castletown, having, as argued by the Rev. J. Quine, been removed after the dissolution (1541), when the furniture, ornaments, and building materials were sold and scattered. A small vaulted passage, left standing at what must have been the west end of the Church, may, Cumming thought, have been connected with the crypt. On one of the key-stones of the arch is a socket for the suspension of a hook, perhaps for a corpse-light. Traces of inhumation have been met with in one corner. In this vault have been gathered a. few carved stones and other relics recently recovered; also a fine coffin-lid, of which the exact original site is unknown. It is of thirteenth century work, and of interest as being the oldest stone monument of English or Gothic architecture in the Island, and, as marking the end of the old type- illustrated by the Celtic and Scandinavian carvings referred to above. It may have been the tomb of Olave the Black, who was buried here in 1237, or of his son Reginald, 1248, or, even more probably, of the last Norwegian King of Man, Magnus, buried in the Abbey in 1265 (fig. 43).

Fig. 43.- Rushen Abbey Coffin-lid.- From full-sized drawing by P. M, C. Kermode.

A square tower remains at the entrance to the Abbey grounds, which, on the east, would be well defended by the river, doubtless in those days deeper and at a lower level. An indication of the former level of the ground appears in the Refectory, now converted into a stable, where the tops of the windows appear almost on a level with the present floor.

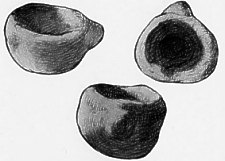

Near by, at the foot of the mill dam, which may have been raised by the Cistercians themselves, is the " Crossag," an example of a thirteenth century bridge, nearly in the same state as it was left by the builders. Its breadth is just Xft. Sin. clear in the centre. At the western end is a small subsidiary arch, somewhat of the Carnarvon type, or square-headed trefoil, but an original portion of the structure, a type of which we have several doorways in Castle Rushen. (One is seen behind the elk in fig. 3.) Some encaustic tiles of perhaps 15th century from Rushen Abbey are shown in fig. 44.

Fig. 44. Encaustic tiles, from Rushen Abbey.

Bemaken Friary in Kirk Arbory (Cairbre), though founded by the Grey Friars in 1373, has scarcely any remains, and none older than the fifteenth century. In the chapel, now a barn, may be seen the arches of the east windows, north door and window, and a south window-the square-headed trefoil. A wall forming the north gable of the farm house, 4ft. thick, may have belonged to the Refectory.

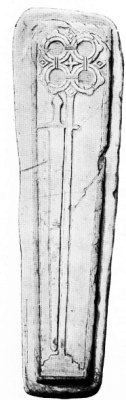

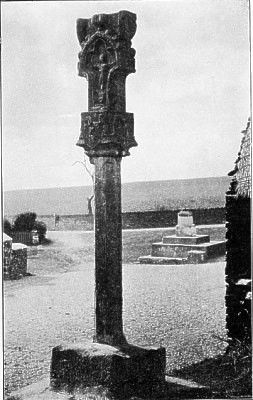

A few of the Parish Churches, such as Malew, Marown, Lonan, and Maughold show portions of walls, lights, &c., of the twelfth, thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries. In connection with the latter Church is the beautiful standing Cross at the gates (see fig. 45), the only monument of its kind in the Island, evidently of about fifteenth century date, and contemporary with the east window, recently removed, and with some other details found in the course of repairs. It is thus described by the Rev. J. M. Neale, in his Ecclesiological Notes (1848)---"A Third-Pointed erection, very perfect and beautiful. It is raised on four square steps-the stone is octagonal; the capital is adorned with four shieldsone the arms of Man, one a mere wheel-tracery, the other two much effaced. From this springs the real Rood, bearing on its four sides our crucified Lord, our Lady and the Divine Infant, St. Bridget kneeling, perhaps about to take the veil, and St. Maughold."

Fig. 45.-East face of standing cross at Maughold. From photo. by G. B. Cowen.

The ruins of two keeils of later date than those already mentioned are well worth preserving. The first, on St. Michael's isle, near Langness, was in ruins in Chaloner's days (1652-60). It is rectangular, 32ft. by 14ft. 8in. inside; the walls, of large and small stones, being 3ft. thick. At the west end is a single bell turret. The door, of which the jambs are rough blocks of limestone, was on the south, and had a semi-circular head. The east window, one lancet, arched; the north has the head out; the south and west were square-headed, the latter two 12in. wide outside, but with a splay inside to 2ft. loin. The foundation of the stone altar may be seen under the east windows. The height of the side walls is only 10 feet. The graveyard measures 64 yards by 33 (fig. 46).

Fig. 46.-Keeil on St. Michael's Island.-From a sketch by Sir H. Dryden.

St. Trinian's, Marown, is at the foot of Greeba, in a meadow by the high road from Peel to Douglas. It measures outside 75 feet by 24; the walls, about Oft. thick, are built of the local clay-slate, with dressings and quoins of red sandstone, and it is of Early Middle-Pointed style. Tlie east window of two lights, acutely pointed, is 4ft. wide; on each side of the chancel was a one-light window. The priests' door was on the north. The nave appears to have had two one-light windows on the north, and one besides the door on the south. The west window was an ogee-headed lancet, and its garble bears a double campanile. The rubble which supported the altar still remains about a foot high. The Stoup is in the east side of the south doorway, inside. There is a hole in the doorjambs as for a bar (fig. 47).

Fig. 47. Keeil of St. Trinian, Marown. From a sketch by Sir H. Dryden.

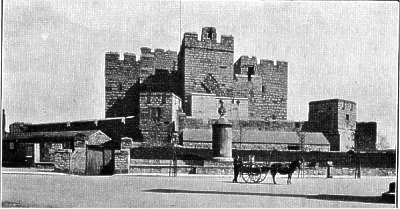

The finest of all the Manks historic monuments is Castle Rushen (fig. 48). According to the Chronicle, Robert the Bruce laid siege to it in 131:3, when Duncan Macdougall held it against him for more than three weeks. The oldest portions of the existing walls are doubtless the underground chambers of the tower at the entrance. The Keep is of the Edwardian type of concentric castles, as distinguished from the solid square keep of earlier ages; some architectural details point to the middle of the 14th century, but so far neither the exact period nor the builder has been determined. Its height at the entrance is 74 feet, the flag-tower 80 feet from the present surface, which has been filled in to a considerable depth. The thickness of the walls is from 7 to 12 feet. At its northern extremity is a lofty portcullis, passing which one comes to an open quadrangular court, with a well in the centre. Outside, at a short distance is an embattled wall 25 feet in height and 9 feet thick, with several square towers at irregular intervals. Exterior to this was a fosse or moat, now filled up, outside of which is the glacis said to have been added by Cardinal Wolsey, when guardian to Edward, third Earl of Derby. On this were three low round towers or redoubts, of which one remains on the north-west side near the harbour. We are indebted to Mr. G. B. Cowen for the general view of the Castle as seen from the Market Place (fig. 48).

Fig. 48. View of Castle Rushen from the South. From photo. by G. B. Cowen.

The clock tower was the old chapel of the castle, about 15 feet square. On each side of the oriel window is a stone ledge on which rested the ancient altar; on the south side of it a piscina, and on the north a small niche (an aumbrie, or equivalent of the credence table) for the sacred elements. A small grated window in the north angle appeared to communicate with a cell, conjectured by Mr. Cumriing to have been the confessional. The clock, with its curious dial, which hides one of the windows, was a present from Queen Elizabeth, and the bell, as shown by the inscription, was supplied by James, tenth Earl of Derby, in 1729.

Some additions to the buildings were made by James, seventh earl, when Derby House was added as a residence. A stone was found there with the letters D and I C, with the date 1645-James and Charlotte Derby, who resided here at that date. It would be very interesting and instructive to have a complete plan made of each floor of the castle. Mr. Armitage Rigby is now preparing such plans, and has kindly allowed us to reproduce here that of the ground floor of the castle (fig. 49)

Fig. 49.-Plan. of Castle Rushen.

Of camps and small earthworks of the Historic period, besides those of earlier date still in use, the oldest recorded are those of Magnus, King of Norway (about 1098), of whom we read in the Chronicon Manniae that he obtained timber from Galloway and from Anglesey and erected many forts in the Isle of Man. That at Baldrine may be an example of this period, with others like it. Some round camps also have been considered Scandinavian in origin, such as that still to be traced at St. Mark's, at the head of the valley where the Silverburn arises, and one which was at Ramsey just north of the Ballure stream, on the brooghs now entirely washed away. Mannan's Chair, in German, and one or two others seem to have been somewhat similar, but on a larger scale; a notable earthwork is that at L'hergyrhenny, on the west shone of Snaefell, known as the Bow and Arrow Hedge. It is 10 feet high on the north side and 15 feet on the south; 12 feet wide at the base and 6 feet at the top. The ditch on the south is 9 feet to 12 feet wide, and can be traced almost right across a neck of land between two deep streams, for about 550 yards.

But the finest of the camps is that encircling the top of South Barrule (formerly Wardfell). On the northern side of the summit are traces of dry stone walls enclosing an irregular area of about 22,000 square yards, the thickness of the base of a wall on the northern side being upwards of nine yards. The approach on this side is an easy ascent; on the south the wall has been much narrower and weaker, and perpendicular to the brow of the cliff, which is inaccessible; it is filled up inside so as to form a raised way or parapet. Some traces of a roadway into the camp are due to the fact that this spot was selected by the officers of the Trigonometrical Survey of Great Britain for the erection of their instruments for connecting with the triangulation of the British Isles.

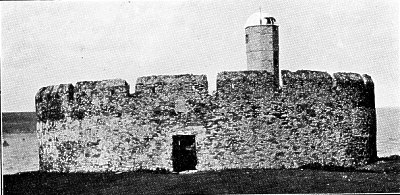

At Ballachurry, in Andreas, is a fort, probably erected by James, seventh Earl of Derby, about 1644. It is rectangular, enclosing a space 50 yards by 40 yards. The earthen walls are six yards thick, with four bastions at the corners, all surrounded by a wet fosse of ample dimensions. About the same date was built Fort Loyal, of small size, to command Ramsey Harbour, which in those days would be at the north end of the Mooragh. The low mound of its foundations can still be traced. Probably remains on Gob-ny-Ronnag, Port Lowaigue, and elsewhere round the coast, were then either erected or strengthened and restored to use. On St. Michael's Isle is a circular embattled fort of stone, over the doorway of which is carved a coronet, with the date " 1647." The walls are 8 feet thick, but not solid; it is badly in need of repair.

Fig. 50. Derby Fort on St. Michael's Isle. From; photo. by G. B. Cowen.

Of loose articles of the Historic period some deserve at least a passing notice. We may consider them under the heads of-Weapons, Coins, Furniture, Ornaments, Implements and Utensils.

As regards the first, we have examples of cannon of the time of Henry VIII. and of Charles I. at Peel, and of Elizabeth at Castle Rushen. At Bishopscourt are two small cannon from ships' longboats taken from Thurot in an engagement off Ramsey at the end of the 18th century, and others in Jur'by and Bride are of the same period. Iron swords and daggers from Maughold Churchyard, and a broadsword and spear from Ballaugh village are in the Edinburgh Museum. " A basket-handled sword of great size and battle-axe " were found in a stone coffin in Patrick; swords were found at Glen Meay, and a sword and spear-head at Ballachrink, Jurby, but we do not know where these now are. An iron dagger-handle from Michael is in the collection at Castle Rushen. A pike-staff found in Ballaugh curragh about 1859 is now lost. Very likely other such articles are in private collections of which we have not heard, and many no doubt have been taken off the Island or lost.

At Peel Castle have been found stores of granite cannon balls, most of which have been recognised by Mr. Lamplugh as of Foxdale granite. A few stone, and one or two small iron cannon balls have been found also at Peel and in the north of the Island. The most notable historic weapon is the sword of state which used to be carried in procession before the sovereigns of Man, and is still borne before the Governor in the ceremonies at Tynwald. This was submitted to the authorities at the British Museum and considered to be of the 12th century. It is said to be exactly similar to that on the tomb of King John, and was thus described (Manx Society, vol. XIX., p. 21) :-" Near the rest on each side are the arms of Man with armour on the three legs, and in the centre of this is a curious triangle . . . In its present state it is three feet six inches and one-eighth in length, but the point having been at some time broken off by improper usage, it was no doubt some four or five inches longer originally," ending probably in a sharp point. Our figure 51 is from a photograph taken for us by Mr. T. Keig, of Douglas.

A memorial of the ancient regal rights and prerogatives of the Island exists in its currency, coined and issued by the Lord with the sanction of the Tynwald Court. No notice is recorded of any insular money till 1679, when Governor Murray's copper penny became a legal tender. Subsequently various supplies of coin in copper were issued by the Derbys and the Dukes of Athol. These were stamped with the three legs and motto, and, on the reverse, the Eagle and Child, with the motto, " Sans changer," or some other insignia of the Stanleys, with the initials of the reigning Sovereign. The Duke of Athol stamped his copper coinage with the letter A, and a crown on the obverse. Our figure 52 is taken from Plate 1. of the Manks Society, Vol. XVII. About 1825, paper cards or tickets, stamped for 1s., 2s. 6d., and 5s. British were legal currency; also copper pence tokens by small bankers in all parts of the country, with one pound notes of private bankers licensed by the Insular Government. Gold and silver coins of Saxons, Danes, Normaus, English and Scottish have been found frequently, and it is stated that when the Mandevilles from Ireland pillaged the Island in 1315 they carried away large quantities of silver money which they found secreted.*

Fig. 51.Manks Sword of State, Twelfth Century.

Under the head of Furniture and Ornaments may be mentioned the stone reliquaries at Peel Cathedral, several rude stone fonts (pre-Reformation), as at Maughold, Bride, Marown, and a beautiful stone holy-water Stoup, 4in. high, and 6in. to 7in. diameter, recently found at a holy well by an ancient keeil on Grenaby, Malew (fig. 53). Very little pre-Reformation Church plate has been found. At Jurby we have a beautiful silver chalice, which was figured and described in the Illustrated Archaeologist, January, 1895. The hall-mark shows it to date from 1521; the bowl is broad and shallow, stem plain and hexagonal, with hollow chamfered mouldings at the junction with knop and foot; knop of six-lobed type, with angel-marks on the points; the foot is hexafoil, and the vertical edge of the base has a border of leaf and flower design.*

FIG. 53. Stone Holy-water Stoup, at Grenaby. From a sketch by B. S. Herdman.

At Malew is a brass Crucifix of the twelfth century, and a silver Paten of 1525. As regards the latter, the Bernicle in the centre instead of an Agnus Dei, or Hand in Benediction, establishes it as pre-Reformation, about 70 others being known to be in existence.

Some encaustic tiles of fourteenth and fifteenth centuries have been found at Rusher Abbey. We figured above some pieces described in " The Reliquary," January, 1885, by the late Ll. Jewitt, Editor (see fig. 44).

Some fragments of stained glass from Peel Cathedral, now in possession of Sir James Gell, have been described in Manx Soc., Vol. XXIX., p. 21. They are chiefly interesting as showing the earliest representation of the three legs.t

A curious wooden Mace in black and gold, now in Castle Rusher, from the collection of the late Mr. Wallace, of Distington, was described by him as having been borne in procession before the Manks Bishops. The remains of a carved oak Rood Screen. from the Nunnery Chapel may be seen in the Museum at Castle Rusher. There is also at Arbory Parish Church an interesting inscription by Abbot Ratclilf, carved in oak.

A few gold and silver ornaments have been preserved; some, as a silver necklace and bracelet, found in Andreas, in 1868, and gold and silver rings and bracelets found in Douglas in 1894, having been claimed as Treasure Trove, are now in the British Museum. A few, like the Mylecraine Silver Cross, and the Gold Whistle shaped like a Cavalier's boot, found in the Fort at St. Jude's, are in private hands. No doubt many have been carried away, lost, or destroyed.

Among implements, utensils and household furniture must first be mentioned the querns,* (fig. 54) or hand-mills (" braaiu "), frequently of granite, which must belong to various periods; some have been recognised as probably of the Iron Age, and some, as the "' Saddle stones," may be a good deal older.

Fig. 54. Manks stone querns in Castle Rushen.

In later historic times the corn was dried in small kilns attached to the farm. Thrashing was performed with a flail (" soost ") composed of two stout and straight branches, fastened together by a thong of hide. The portion held in the hands was called " laneraghyn," and the head or part which beat the corn, " slatt-boost." These have gone out of use within the last twenty years. Two men or women would -work together, having a. sheaf of corn spread out before them on the floor, which in that spot was made particularly strong and thick, as may still be seen in some old barns. In winnowing a sieve or tray, " Dollan-benalt," was used in the open air. This was made by bending a thin band of wood, the ends overlapping and tied together by ineans of a tendon run through small holes bored in the wood. Over this was spread a sheep or goat skin, sewn on to the band by cords plaited through the skin and holes in the wood. Being filled with grain this was carried to the door or into a field, a sack or something being spread underneath. The dollan was moved gently back-ward's and forwards so that the wind might blow the chaff away: In grading the grain, and in the process of meal sifting, similar trays, but perforated, were used, holes being made in the skin by boring with a small red-hot iron bar. The " Peick," very much like the dollan, but smaller and deeper, was used for holding bonnags, cakes, meal, and such like, and was generally kept on the " latts " in the kitchen.

Straw taken from the flail without being broken (" gloyee ") was turned into rope, " suggane." Such ropes of straw and bay are still used to secure thatches of cottages and stacks. They are made by " twisters," rods or branches of willow or ash, bent in V-shape, the thicker end elongated and revolving inside a hollow wooden handle. The other end is bent by a string tied to its point, and attached to the first at the point where it enters the handle. A portion of the straw or hay being made fast to the loop, the bent rod is twisted by one man walking backwards, while the other is engaged in teasing out the hay gradually and evenly.

The long narrow spade used for digging peat is now seldom to be seen. Another implement gone out of use was the push-plough, of which there is a single example in Castle Rushen. This was used for breaking up hard ground before ploughing, much as the grub~ber is at the present time. Ling-drawers are stili to be met with. These resemble sickles, some being toothed, some plain. Blunt sickles also were used for drawing gibbons out of the sand. The " Lister " was a straight-pronged trident used for spearing flukes. Straight-pronged iron fomlis, or " grips," were made by the local blacksmiths for farm purposes also before the introduction of the modern curved steel forks. These were used also in digging gibbons (the lesser sand-eel, Ammodytes tobianus).

In old clays the "fidder," or weaver, was an important personage, most parishes having one or more handlooms, but now the modern mills have taken their place. The old spinning-wheels also are fast disappearing. They all had the " quiggal " or distaff attached to them, so that the same wheel could be used either for flax or wool. Flax, commonly grown in the Island until some 50 years ago, when cut, was left lying for some time in water, then sent to the tuck mill, " Myllin walkee," to have the skin or bark torn off, after which it was combed by a " heckle " into the condition of tow, when it was ready for spinning. Sometimes the carding of flax would be done at home, the heckles used, of which some examples may be seen in Castle Rushen, being exceedingly primitive. A " swift " was required for winding the balls off into hanks, which were then ready for weaving into linen.' The spinning of wool for stockings or cloth was somewhat similar, only the quiggal was removed from the wheel, the " rolls " being kept on the knee. After the wool from the sheep had been washed and picked, it was carded with combs, " threden olley," and then, with a quick turn of the wrist, made into short rolls with the back of the combs. When two spools of wool had been spun, they were put on the " clowan broachey," reel bobbin or wheel spools; the spinning wheel being then turned the reverse way, twisted them together into strong " threads," ready for knitting into stockings, or for weaving in the hand-loom into cloth or dress material. If the thread was required in hanks, as it would be for making cloth, a " crosh-lane," handcross, would be used; this crosh-lane was made of wood somewhat the shape of an anchor. The thread was put round it and thus formed into hanks. If, again, hanks were required in balls, there was the " chrown thross," winding blade, for that purpose ; in shape this was like the sails of a windmill, and, fixed in a wooden stand, revolved in something the same manner. One kind, after 60 revolutions, made a little " clic," showing that a certain quantity of wool was wound, and then started afresh.

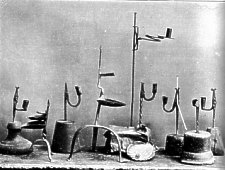

With regard to lighting arrangements, an original natural lamp used here until quite recently was the " Tanrogan," or large scallop (Pecten maximus), the hollow upper shell of which made a natural saucer in which a wick of rag or rush would lie in solid or liquid grease, sometimes lard, sometimes fish oil, or goose-grease. The

" Cruisie " is very rare. It has an oil vessel formed with a spout from which the wick " bitte," projects, and hangs from a hook provided with notches by means of which the vessel can be tipped forward gradually as the oil burns down. A second and larger vessel fixed below is to catch the drippings of the oil. The iron rush and candle holder (fig. 55) is more common, but fast disappearing. For these, the rushes were cut in the summer, the peel removed excepting a narrow rib running from top to bottom, left to support the pith, and the cores thus obtained dried and bleached in the sun, while the strips of peel were twisted to form lankets for sheep. The cores were then dipped in scalding grease until thoroughly saturated, and after being allowed to cool were ready for use. The most simple type of iron holder for these rushlights had a thin point of the iron., about an inch long, split off for the purpose. The usual form bad the lower end of the iron stand, which was somewhat pointed, inserted for steadiness into a block of wood, generally cylindrical, or very slightly shaped. The upper end, about an inch in length, formed, with another piece of iron moving on a pivot, the jaws or nippers to hold the rush, the necessary pressure being given by a bent lever and weight at the other end. In a development of this the weight was formed into ~a ring or socket, which serves also to hold a candle (fig. 55). In general, however, this ring is deepened and the bottom closed. The total height of the holders was generally from nine to twelve inches; sometimes it is set on three or four iron legs instead of in the wooden block. At Orrysdale is a curious spiral form in which the candle was raised or lowered by twisting a pin round and round in the spiral. Sometimes the holders were made to hang from a nail. Later, candles were cast in moulds made by local tinsmiths. These, which are now scarce, were long hollow cylinders tapering to a cone at one end, the tip open to allow the wick to be set centrally in the mould. Later moulds had a funnelshaped reservoir at the top to prevent the melted tallow from overflowing.

Fig. 55. Old Manx Tanrogan lamp, cruisies and rush-light holders-

from a photograph.

For the loan of this block we are indebted to the courtesy- of the

Publisher of " The Antiquary."

Home-brewed " jough," made in many farmhouses, was kept in deep, narrow, earthenware " crockans," a large wooden plug filled the top, and the beer was drawn off by a smaller one near the bottom, called the " thalbane pluggane." These crockans differed in size and shape, but were all tall and narrow, holding some two or three gallons. The round wooden butter boa, taken by the fishermen to " the herrings," would hold a pound of butter. The owner's initials were often roughly cut on the top of the lid with a knife. This and flat cakes, of flour or meal, " berreenyn," baked upon a "Josh," or baking-stone, the circular flag placed over a peat fire, were all they would take with them, the rest of their fare consisting of the herrinngs which they caught. As stated by Waldron (Manx Society, XI., 49), " the first course of a Manks feast is always broth, which is served up, not in a soup dish, but in wooden piggies, every man his mess. This they do not cat with spoons, but with shells, which they call sligs, very like our mussel shells, but much larger." The " piggies " are locally known as " noggins " -tumbler-shaped wooden cans, about four inches high, with one stave left projecting for a handle-in fact, the Scottish "luggie." Horn spoons, about nine and five inches long, were made locally, but are now rarely to be seen. Spoons of lead and pewter were in use until about forty years ago, and several of the moulds are still preserved. They were made by old women, who used to go round the parish carrying their own moulds and crucibles or " cressets." The spoons were about seven inches long, and were made, or " run," at a charge of a Halfpenny each. The inside of the mould was smoked in the wick of a tallow candle; this prevented the lead sticking, one smoking being sufficient for six spoons.

It is difficult now to get a pair of " carranes," the shoes worn till about 50 years ago. They were made of tanned, and sometimes of undressed, hide, that of a heifer making about four pairs. The smooth side was worn neat the foot. They were tuned up all round, and laced at the back of the heel with a thong of hide.

Settles of oak or deal were formerly to be seen in every chimney nook. There was but little carving, sometimes the back was open work, but generally plain. A few oat: chests and some old armchairs of the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, are in the hands of private owners; and it would be interesting to have them all figured and described. Miss Christian, Baldromma, whose will was proved within the last few months, has set a good example by bequeathing such a chair, with the date 1685 carved upon it in bold relief, to Mr. P. M. C. Kermode, for the Manks Museum, in which she knew he took so great an interest. If this example were more generally followed we cannot doubt but that a very interesting collection would be formed illustrating the past history of the Island.

If the foregoing pages in any degree help to the establishment of such an. institution as a well-equipped Insular Museum, by arousing interest in it, and by suggesting the character of its collections, so far as Antiquities are concerned, and, perhaps, by inducing our readers to secure for it before it becomes too late such articles as are illustrative of the past history of the Island, we shall feel that this little book has not been published in vain.

Fig. 56.-Old type of long Manks cottage.

From an unpublished sketch be Sir H. Dryden.

C. '1'inlitn; S Co.. Ltd.. Printers. Victoria Street. Liverpool.

1 Yn Lioar Manninagh, III., p. 405.

2 List of Manks Antiquities. P. M. C. Kermode. Manx Society, XVIL

3 Manx Soc., XV., 107-109. Yn Lioar Manninagh, II, 227.

4 Excepting perhaps a seal in the British Museum, A.D., 1300. (See Oswald ; Vestigia.)

5 One of these bears a simple cross-shaped design in low relief.

6 See an interesting article by Miss A. M. Crellin, in Yn Lioar Manninagh, Vol. II, p. 265..

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received

The Editor |

||