from particulars supplied by Mr. Irving and The 'Mongoose' himself

(Photograph by F. W. Bond)

[From The Haunting of Cashen's Gap ,1936]

NEWS of the mystery first reached London in October 1931, when paragraphs concerning a Manx prodigy called a 'man-weasel' appeared in the Press. Thus the Daily Sketch published a photograph of Irving's cottage, with the caption 'The "Talking Weasel" Farm', and the Daily Mail and other journals briefly reported strange events at Doarlish Cashen. The northern dailies took a greater and more sustained interest in the affair, because the talking animal was a near neighbour, and naturally attracted more attention than he did in London.

Early in 1932 the Manchester Daily Dispatch sent a reporter to the Isle of Man in order to investigate the mystery on the spot. Their representative was fortunate in hearing the 'weasel' speak on his first visit. We cannot do better than quote his own words as published in the Dispatch:

The mysterious 'man-weasel' of Doarlish Cashen has spoken to me to-day. Investigation of the most remarkable animal story that has ever been given publicity-a story which is finding credence all over the Island-leaves me in a state of considerable perplexity. Had I heard a weasel speak? I do not know, but I do know that I have heard to-day a voice which I should never have imagined could issue from a human throat; that the people who claim it was the voice of the strange weasel seem sane, honest, and responsible folk and not likely to indulge in a difficult, long- drawn-out, and unprofitable practical joke to make themselves the talk of the world; and that others had had the same experience as myself.

Mr. Irving related to the reporter the story of how the animal had taken up his abode at the farm, but denied that the place was 'haunted'. 'There are no spooks here,' he cried. The news- paper man was impressed by what he had heard at Doarlish Cashen, especially as the 'weasel' gave him a 'tip' for the Grand National!

But, after sleeping on it, the Daily Dispatch representative became apparently less convinced that the manifestations were abnormal, and considered that the 'animal' might be a fantasy of Voirrey's childish imagination. In his next report (published the following day) he says:

Does the solution of the mystery of the 'man-weasel' of Doarlish Cashen lie in the dual personality of the 1 3-year-old girl, Voirrey Irving? That is the question that leaps to my mind after hearing the piercing and uncanny voice attributed to the elusive little yellow beast with a weasel's body. Its alleged powers of speech have caused a widespread sensation. . . . Yesterday I heard several spoken sen- tences and was told that these noises were made by the 'man weasel'. The conversation was between the 'weasel-voice' and Mrs. Irving, who was unseen to me in another room, while the little girl sat motionless in a chair at the table. I could see her reflection, although not very clearly, in a mirror on the other side of the room. She had her fingers to her lips. I kept my eyes on the face in the glass. The lips did not move, so far as I could see, but they were partly hidden by her fingers. When I edged my way into the room, the voice ceased. The little girl continued to sit motionless, without taking any notice of us. She was sucking a piece of string, I now saw.

It is interesting to note that this reporter actually heard the 'voice' when the girl was in his presence, a few feet from him-an experience hardly ever vouchsafed to later witnesses of the phenomenon.

|

|

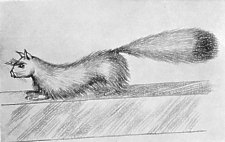

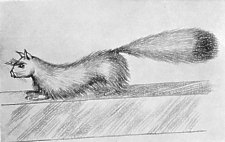

| Drawing by George Scott of Gef from particulars supplied by Mr. Irving and The 'Mongoose' himself |

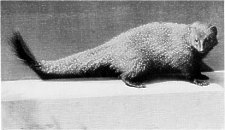

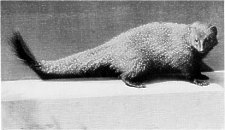

Photograph of a grey mongoose at the zoological gardens (Photograph by F. W. Bond) |

Hard upon the heels of these newspaper reports came a letter to Mr. Harry Price (who was then Director of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research) giving in greater detail an account of the curious manifestations which were puzzling the Manxmen. This was in February 1932. The writer was Miss Florence Milburn, of Glenfaba Road, Peel, and she told an extraordinary story. In her letter (February 12th 1932) she stated that in September 1931 Mr. Irving noticed a strange animal among the fowls in the farmyard. In appearance it was similar to a weasel, with small body, long bushy tail, flat nose, and yellow in colour. Being arrested by its ability to bark like a dog, then mew like a cat, Mr. Irving imitated the cries of various familiar farmyard animals, whereupon the stranger repeated every one correctly without hesitation.

A little while after-Miss Milburn continued- the Irvings heard a loud thumping on the stained wooden match-boarding with which the rooms of their house are panelled, and it proved to be the animal trying to attract attention. The letter contained a good deal more about the 'weasel' and his doings, and Mr. Irving's address was given. Mr. Price wrote to him.

In his reply (February 22nd 1932) Mr. Irving gave a short account of the finding of the animal and a description of the alleged manifestations. He says:

The animal in question has been seen by myself and daughter of 14 [Voirrey], in one of the two bedrooms of my house, on several occasions in the month of October last. My daughter has on two occasions in January 1932 seen its tail only, in the small back kitchen, in a hole in the wall. My wife has seen it on one occasion only in October. The colour is yellow, not too pronounced, after the ferret. The tail is long and bushy, and tinged with brown. In size, it is about the length of a three-parts grown rat in the body, without the tail. It can, and does, pass through a hole of about 1½ inches diameter. I, personally, am strongly inclined to the view that it is a hybrid between a stoat and a ferret. The bushy tail is not that of a stoat, and the size certainly half that of the ferrets I have examined. . . . My daughter says the face is all yellow, and the shape is more that of a hedgehog, but flattened at the snout, after the fashion of the domestic pig.

Mr. Irving stated that though the three members of his family had heard it outside his house, not one of them had ever seen it outside. This account is at variance with the story told by Miss Milburn, who informed Mr. Price that 'the animal was first seen in the farmyard among the chickens'.

In the same letter to Mr. Price, Mr. Irving says:

We were first made aware of its presence in September last by its barking, growling, spitting, and persistent blowing, which I under- stand is the procedure of the weasel family. . . . Now as regards its speaking ability, it did not possess this power until the first week in November last; but now converses, incredible as it is, as rationally as most human beings. . . . Its first sounds were those of an animal nature, and it used to keep us awake at night for a long time as sleep was not possible. It occurred to me that if it could make these weird noises, why not others, and I proceeded to give imitations of the various calls, domestic and other creatures make in the country, and I named these creatures after every individual call. In a few days' time one had only to name the particular animal or bird, and instantly, always without error, it gave the correct call. My daughter then tried it with nursery rhymes, and no trouble was experienced in having them repeated. The voice is quite two octaves above any human voice, clear and distinct, but lately it can and does come down to the range of the human voice. . . . It is not a prisoner, and I have no control whatever over its movements, and I can never tell whether it is in or not. It announces its presence by calling either myself or my wife by our Christian names. . . . It apparently can see in the dark and describe the movements of my hand. Its hearing powers are phenomenal. It is no use whispering: it detects a whisper 15 to 20 feet away, tells you that you are whispering, and repeats exactly what one has said.

Mrs. Irving added a footnote to the effect that 'my husband's statements are perfectly correct'. The Irvings decided to tolerate the animal, though previously the farmer tried to kill it by means of gun, trap, and poison. It eluded all attempts at capture, dead or alive.

It can be imagined that the receipt of the letter caused considerable interest among the officials of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research, and Mr. Price decided to send a representative to Doarlish Cashen in order to make some inquiries on the spot. Captain Macdonald, a well- known racing motorist and business man and a member of the National Laboratory's Council, accordingly crossed to the island and visited the farmstead, where he arrived at 7.30 p.m. on February 26th 1932. He afterwards furnished Mr. Price with a report (dated February 28th 1932), from which the following information has been extracted:

I sat in a corner of the living-room, and listened to Mr. and Mrs. Irving again giving me their story, more or less in agreement with what we already had been told. Then they showed me various cracks, and holes in the woodwork of the room which the animal used (so they said) to see who was there. We sat and talked until just about 11.45 p.m. and as nothing had taken place, I suggested making my way back to Glen Maye. . . . Mr. Irving said he thought he had better pilot me home, so we put on our overcoats and set forth. Just as I had shut the door of the house we heard a very shrill voice from inside scream out 'Go away. Who is that man?' Mr. Irving gripped my arm and said: 'That's it!' I heard the shrill voice continuing, but was unable to catch exactly what it was saying. We remained out- side for five minutes, but I was so cold that I told Mr. Irving that I must either go in again, or go on down the hill. We decided to go in, so I stalked back, and quietly got in the room, when the voice at once ceased.

Captain Macdonald stayed for fifteen minutes, but hearing nothing further, returned to his hotel at Glen Maye.

Next morning (February 27th) Captain Macdonald returned to the farm at 10.30, in order to have a long day with the 'weasel', as they still called it. Mr. Irving greeted him with the news that the animal had been talking that morning, and had promised to speak to him in the evening provided that he 'made a promise to give Voirrey a camera or gramophone'. The report continues:

I was also informed that I had to sit in a recess in the room as the animal said it had been looking at me the previous night and did not like me; again, it also said that it knew that I did not believe in it, so I would have to shout out in the early evening that I did believe in it, etc.

At 5.30 p.m. Mr. Irving suggested a cup of tea, so Voirrey prepared some, and Captain Macdonald, Mr. Irving, and his daughter sat down at the table (Mrs. Irving had gone to Peel).

While we were talking, something was thrown from the panel behind Mr. Irving. It struck the teapot, or possibly a cup, and Mr. Irving said: 'That's the animal.' We examined the cloth and found a large packing-case needle, which I picked up and gently threw at the teapot, when exactly the same noise was again made, Mr. Irving saying that it constantly threw things at the family. At 6.15 p.m. we heard plates and similar things being moved in the small scullery. No one was there. A little later, again the same noise, and again no one there, but we found a little stream of water running from a small hole in the wall, which Mr. Irving said was the animal performing its natural functions. I saw no sign of rats or mice, but Mr. Irving said that there were plenty of weasels about. At 7.20 Mrs. Irving returned from Peel and was astonished to hear that the animal had not spoken, in view of its morning promise.

After waiting a short time Mr. Irving asked his wife to 'go upstairs and see if you can make the creature begin', remarking to Captain Macdonald: 'If we can get him to start upstairs he will then come into this room.' Accordingly, Mrs. Irving and Voirrey went up to the bedroom immediately above the living-room. Captain Macdonald continues:

In about three minutes there was a shrill scream, Mr. Irving saying: 'There it is.' Then Mrs. Irving said: 'No, come on and talk!' whereupon a very shrill voice started talking in the bedroom, and kept on talking to Mrs. Irving for 15 minutes. I then shouted that as I believed in the animal, would it come down? I received a shrill reply: 'No! I don't mean to stay long as I don't like you!' . . . I then quietly crawled up the dark staircase, but by sheer bad luck, and owing to one of the stairs being broken, I slipped and fell, making a terrible noise-the result being that the shrill voice screamed: 'He is coming!'

Though Captain Macdonald stayed until midnight, the 'voice' was not heard again, and he went back to his hotel. Captain Macdonald concluded his report to Mr. Price by rightly remarking that as Mrs. Irving and her daughter were upstairs when the voice was heard, the evidence for its abnormality 'was not of much value'.

For the next three years (except for a break in 1933) the doings of the animal were faithfully recorded in the form of letters sent to Captain Macdonald. Copies were deposited with the National Laboratory of Psychical Research (which, in June 1934, became the University of London Council for Psychical Investigation). The adventures of the 'weasel' might have been taken from the pages of A Thousand And One Nights, so remarkable are the fantastic improbabilities which the record contains. All these adventures were related to the present writers when they visited Doarlish Cashen in July 1935, and what they were told tallies in almost every particular with the incidents recorded in the scores of letters which Captain Macdonald received from Mr. Irving. The following pages chronicle the history of the animal from the first visit of Captain Macdonald in February 1932 to his second investigation in May 1935

It was in March 1932 that Mr. Irving discovered that the animal was an Indian mongoose. About twenty years previously a farmer named Irvine, whose land was in the vicinity of Doarlish Cashen, procured a number of mongooses which he turned loose in the fields, in order to kill the rabbits. Mr. Irving concluded that his talking mongoose was a descendant, but was afterwards informed by the animal himself that he was born on June 7th 1852, and came from Delhi and had been chased and shot at by natives! It was about this time that Mrs. Irving saw it outside the house. Voirrey also tried to photograph it, the animal sitting on its hind-quarters and posing for her. The girl not being quick enough, the mongoose vanished. But the farmer was successful in inducing it to eat chocolate, bananas, and potato pie, which were left in convenient spots overnight.

In June 1932 the mongoose became on more familiar terms with his hosts, especially Mrs. Irving. He was persuaded to run on the crossbeams and show himself more. They discovered that his front feet resembled a human hand, with three or four fingers and a thumb, which gripped Mr. Irving's fingers as in a vice. Mrs. Irving, being bolder, stroked his head and back and felt his teeth. This was while the animal was on the cross-beams in the upper part of the house. At about this period the mongoose began to kill rabbits for the Irving family, perhaps in exchange for his board and lodging. Having killed a rabbit, he would tell Irving where he had placed it-generally in a convenient position near the house.

The mongoose usually called Mr. Irving 'Jim' or 'Pots', and one morning in April 1932 the farmer was awakened at 5 a.m. by the animal calling: 'Jim, Jim, I am sick!' and it could be heard vomiting behind the panelling. It was discovered that he had stolen some unsuitable food in a cottage eight miles away. These journeys were not infrequent, and often he would slip away for a few days"holiday'. Sometimes he would bring something home in his mouth: a paint-brush, pair of pincers, a pair of gloves, etc. He informed his hosts that he had found these in the road. He would frequently carry small objects about the house, and throw them into the rooms. He was especially fond of a ball, which he would bounce on top of a boxed partition (his 'sanctum') to the tune of a gramophone.

In the summer of 1932 the Irvings discovered that their guest knew several languages. For example, the animal called out: 'Ne pani amato aporusko', which was recorded phonetically. It was supposed to be Russian. Then he sang a line of a Manx hymn: 'Moyll jee yor chiarn lest and choraa.' This was taught him by Mr. Irving.

The Irvings called their prodigy 'Jack'. But during the summer of 1932 this was gradually softened to 'Gef', and the animal said he liked the name. So, to our readers, the mongoose will henceforth be 'Gef'.

During the late summer and autumn of 1932 Gef, if we may use the term, 'dug himself in', and became an intimate and valued member of the Doarlish Cashen household. Like members of other households, he sometimes became 'difficult' and did not always see eye to eye with Irving's relatives. For example, Mr. Irving has an elder daughter Elsie, and Gef took a violent dislike to her. Elsie is married and sometimes visits her father. But Gef told Mr. Irving quite plainly that if Elsie took up her abode in the cottage he would go away. During Elsie's infrequent visits the animal will not speak. Once he was asked whom he liked best, Mr. Irving, Mrs. Irving, or Voirrey. 'If one of us had to die, which would you prefer?' He replied: 'I do not want any of you to die. I like you all, but don't let us talk about death!' Gef appears to have a real affection for Voirrey.

By the end of the year 1932 Gef had become very proficient in killing rabbits for the Irving family, and the faunal equilibrium of the district was in danger of being upset. Often at breakfast time he would call out that he had killed a rabbit, and give the precise spot where it was to be found. He said he killed them by the throat, and they certainly appeared as if they had been strangled.

Although Gef was very infrequently seen outside of the farm-house during the summer of 1932, he began to absent himself from home. He would take an occasional holiday for a day or so, and, on his return, he would say where he had been. For example, he visited Ramsey cattle show and stayed away for two days (August 3rd to 5th). Ramsey is twenty miles from Doarlish Cashen. He was again absent from August 9th to 13th. Though out and about, he was seldom seen on the roads by any of the family. But on October 22nd 1932 he made his presence known by throwing stones at Mrs. Irving as she was returning from Peel. She shouted: 'Is that you, Gef?' He answered: 'Yes, Maggie the witch woman, the Zulu woman, the Honolulu woman!' This was rather rude of him, but they excused him because he was so excited at the return of his hostess. A few days later he made amends by finding a lamb that Irving had lost. It was found exactly at the spot that Gef had indicated.

By Christmas 1932 Mr. Irving had discovered that the forefeet of Gef were much larger than the hind feet. Not only were they larger, but they had the appearance of human hands, with extensile fingers. He gathered these facts from impressions in the dust which the animal made during his nocturnal rambles about the house. Gef admitted that he had three long fingers and a thumb, and said they were 'as large as a big doll's hands'. The fact that he frequently picks up such small and flat objects as coins, pins, etc., rather points to his having some sort of fingers on his forefeet. A set of paw prints in plasticine and dough which the present writers received after their visit (see Plate VI) confirms Gef's statements. Not only does he claim to have hands rather like human beings, but he uses them in the same way. 'Doubters' (those who do not believe in Gef) are painfully aware of this, as small objects, stones, etc., are thrown at them if they do not 'believe'. As a variant Gef sometimes spits at them through a crack!

If Gef is a mongoose, his food is decidedly that of humans. Captain Macdonald sent Voirrey a box of chocolates. Gef, with his eye to a squint-hole, saw the box arrive. A little later, when Mr. Irving asked Gef if he were hungry, he said: 'Yes, I will have some of Captain Macdonald's chocolates; a nut and a black paradise and a muck sweet!' To Gef, 'muck sweets' are the plain boiled sugar sweets, highly coloured. Gef refuses to touch mongoose food.

Gef celebrated the New Year of 1933 by absenting himself from home. He would often spend an entire week away from Doarlish Cashen. Once he said he had been to the omnibus depot at Peel, hiding under the floor, and listening to what the men were saying. He returned to the farm and told the family about his adventure, and repeated some phrases in the Manx tongue. On his next visit to Peel, Irving called at the depot and was told that an old man had been there, speaking the Manx language-a linguistic feat that only one Manxman in five hundred is now capable of. Gef frequently visits Peel and tells the Irvings what the people there have been doing and saying. On one occasion-it is alleged -he accurately described what a man and his wife had for their supper, and what their conversation was about.

There is a curious hiatus in Irving's record of Gef's life at Doarlish Cashen, as chronicled in letters to Captain Macdonald. The break in the 'diary' lasted from February 1933 until April 1934. The mongoose was not lying dormant, or anything like that: the farmer simply omitted to inform the Captain of the daily doings of his prodigy. As a matter of fact, Gef was very much alive during 1933, and, as Mr. Irving pointed out when he resumed the correspondence, 'our joint and various experiences are too wonderful for words'. He confirmed this when he discussed the 1933 period with us.

During the year 1933 Gef became much tamer, and allowed Mrs. Irving to place her finger in his mouth and feel his teeth. He also shook hands with his hostess, when the three long fingers and a thumb were plainly seen. She told her husband that he gripped her hand like a vice. Mrs. Irving also saw him once out of doors, and her husband, on different occasions, caught two glimpses of him as he swiftly darted across a gap in one of the sod hedges with which the farm is surrounded. The animal was distinctly annoyed at being seen and on both occasions called out: 'I did not intend you to see me. Out of friends for seeing me!' Though so seldom seen outside the cottage, he was often to be found squatting on the cross-beams of the roof. It was here that he took his food: chocolates, bananas, biscuits, lean bacon, sausages, potato pie, etc. Though sitting on the beam, the animal was careful not to expose the whole of his body at one time. He said he was desperately afraid of being caught.

It was during 1933 that Mr. Irving confirmed his opinion that the animal could read. From a squint-hole behind the panelling Gef would call out the name of any book, newspaper, or periodical that a member of the household might be reading, and he was always right. Once Mr. Irving was reading the Liverpool Post when Gef shrieked out: 'I see something!' Upon being asked what had disturbed him he said: 'I see a name that makes me quake, that makes me shake!' Irving scanned the paper, but could see nothing that might have alarmed the animal, who again cried out: 'Look in the deaths!' Irving did so, and found that a man named Jefery had died. In brackets was the word 'Jef'. This coincidence had not been noticed until the mongoose screamed his fright.

At about this time it was discovered that Gef could understand the deaf and dumb language. Out of curiosity, Mr. Irving made signs with his fingers and the animal guessed the word before it was completed. Another word was tried, but Gef exclaimed: 'Do it again. You went too hellish quick!' Another faculty which, it is alleged, Gef developed in 1933 was a sort of clairvoyant one. For example, if Mr. Irving happened to be returning from Peel, Gef would prognosticate his arrival at the cottage to a minute. When her husband was half a mile away Gef would exclaim to Mrs. Irving: 'Jim is coming', and 'Jim' always came. This was so uncanny that it was suggested to him that he was a spirit. He denied the soft impeachment and explained that he did it by 'magic'. 'If I were a spirit, I could not kill rabbits,' was his argument. And he continued to kill rabbits, which, after strangling with his hands, he left at convenient spots. Usually the rabbits were on their backs with their four feet in the air. But Gef cannot be relied upon to tell his hosts exactly what he is, as at various times he has called himself a 'tree mongoose', a 'marsh mongoose', and an 'earthbound spirit'. This last description is a purely spiritualistic term. The Irvings think that he is afraid of death.

Gef suddenly took to singing and speaking in strange tongues. We are told that 'the voice is extremely high pitched, above the human range, with a clear, sweet tone'. Sometimes, in the still of the evening, Irving would hear Gef softly practising the Tonic Sol-fa scale. Then he would sing a hymn or two, or a song. It is thought that he picked up the Tonic Sol-fa at a local school which, apparently, he attended for singing lessons. He began to sing more and more: songs, hymns, and ballads. Some of these the Irvings knew, some were new to them. His singing became almost a nuisance. Later, he danced on top of his 'sanctum' to the tune of a gramophone record.

There is still some doubt as to Gef's antecedents, and where he was before attaching himself to the Irving household. He said he came from Delhi; and, to test him, Irving asked him to speak Hindustani. The following list of words spoken by the animal at various times was sent to us in September 1935. The vocabulary is not an extensive one, and some of the words are familiar even to schoolchildren: Allah, ballah, bigontee, tishoo, charboo, Yogi, punkah, rani, maharajah, nabob, etc. It is curious that Gef knows so little of any Indian language, and so much English-and Manx. Once, when Irving was not very quick at hearing something the mongoose said, Gef retorted: 'You are as thick in the head as a lump of kauri!' Irving states that the word kauri is a Maori word for a tree and its gum. It is apparent that Irving must have used this word in conversation with his family, and that Gef thus learnt it from him.

It has been mentioned that, from his hidingplace behind the panelling, Gef is able to peruse journals, letters, etc., while being read by the Irvings. But it was discovered that he also does a little independent reading of newspapers, perhaps when the family has retired for the night. The question was raised whether Mr. Price should accompany Captain Macdonald on his next visit. Immediately Gef heard their names he screamed out: 'The two spook men!' and began to make fun of the name 'Price'. Of course, this was not difficult even for an educated mongoose. Then he called out: 'Ask Harry Price whose was the invisible hand that scattered the violets about the room at night.' He continued: 'You know, Olga and Rudi Schneider.' Irving declares that although he had seen in the Press an account of Mr. Price's investigation of Rudi Schneider, the incident of the violets and the alleged spirit hand was quite unknown to him.

But an account of this particular seance had appeared in The Times' and other papers, and apparently Gef had read all about it. Although the mongoose had never been introduced to Mr. Price, and did not know him except by repute, Gef appeared a little afraid of him. When it was suggested that both Mr. Price and Captain Macdonald should visit Doarlish Cashen, Gef said that the Captain was welcome, 'but not Price. He's got his doubting capon!' In October 1934 another reference was made to Mr. Price: 'I like Captain Macdonald, but not Harry Price. He's the man who puts the kybosh on the spirits!' He also said that he had seen Price's photograph in the papers 'and did not like him'. But psychical research is not the only subject which Gef studies in the Press. As we have seen in the first chapter, Voirrey has an intimate knowledge of the various makes of motor-cars, and takes a great interest in them. So, apparently, does Gef. He worried the life out of Irving as to the make of car owned by Captain Macdonald (who is a well-known motorist). Was it a 40 h.p. RollsRoyce 'Phantom'? It would be interesting to know whether Gef acquired his interest in cars from Voirrey, or vice versa.[1 For May 7th 1932.]

Gef is careful not to kill rabbits out of season. By June 1934 he had accounted for forty-seven,and then stopped, owing to their breeding and the warm weather. But as the animal wished to make himself useful during the close season, he busied himself with finding the eggs which Irving's ducks laid in out-of-the-way places all over the farm. Having laid the eggs, the ducks promptly covered them up. But clever Gef nosed around and smelt them out, uncovered them, and reported to Mr. Irving the precise positions where they were to be found. The farmer complimented the animal on his industry and sagacity, and remarked: 'What is a leprechaun?' 'A goblin,' replied Gef. 'And what is a pookaun?' 'Another kind of goblin,' said Gef, who, it will be gathered, knows something about Irish folklore.

If laughter indicates happiness, Gef must be supremely contented in the bosom of the Irving family on that lonely Manx upland. He laughs all day. He possesses an extensive repertoire of laughs. To quote Irving's description: 'Sometimes it resembles the tittering laugh of a precocious or mischievous child; at other times I would say it was the chuckling laugh of an aged person, and another distinct type is one which I would say was satanic laughter, or the laughter of a maniac. We all have a most intense dislike to this last laughter, as it is very trying. But, fortunately, we do not get this kind very often.'

Sometimes his laughing is not very sympathetic. Mr. Irving was complaining of a minor ailment when the animal 'laughed like the very devil' and said: 'Hey, Jim, I've got "joint evil" in my tail.' This particular complaint is common to young foals, and Gef must have acquired the expression from the farmer. His knowledge of medical terms is considerable, and once he reeled off the names of some rather obscure diseases. And he is not unacquainted with the British Pharmacopoia. Returning from one of his rambles in the fields, he remarked that he had just consumed a young partridge. Mrs. Irving said she did not believe him. Gef retorted: 'I will vomit it up if you will give me some ipec. wine!'

It is rare for Gef to get his meals out, and after one of his prolonged trips he returns home famished. In July 1934 he was away for four whole days. The family wondered if he were ever coming back. Mr. Irving had just retired for the night when he was startled by a rapid succession of blows on the panelling just behind his head. (Mrs. Irving was downstairs and Voirrey was in bed.) The blows made the room vibrate. Suddenly a squeaky voice cried out: 'Hullo, everybody!' Irving pretended to take no notice. More blows behind his head. At last the farmer spoke to Gef, who shrieked out: 'You devil, you heard me before!' Just at that moment

Mrs. Irving entered the bedroom and chided Gef, asking why he had stayed away for so long, and why he had returned. The mongoose replied rather perkily: 'Well, it's my home!' adding, 'What about my chukko?' (meaning food). So Mrs. Irving fetched him some lean bacon and biscuits and placed them on a beam within his reach. The farmer and his wife could hear him munching the biscuits and talking at the same time. According to the Irvings, an outstanding feature of this remarkable case is Gef's ability to thump the panelling all over the house from, apparently, one spot. When he is annoyed or wishes to attract attention, he bangs the wooden boards of each room in quick succession and with lightning rapidity. The fact that the whole house is panelled, and that there is a space of some inches between the boards and the walls (which are two feet six inches thick) means that the interior of the house is like a vast speaking-tube, with panels like drumheads. It must be extremely difficult to determine the exact location of any sound made inside the house. The Irvings found it difficult to locate Gef's voice at any one moment, and, when they speak to him, they just talk to the four walls (unless he happens to be visible on a beam). Sometimes when Mr. Irving is speaking to the animal his (the farmer's) eyes will unconsciously rest on that part of the panelling behind which Gef is hiding. Then Gef becomes very perturbed and cries out: 'You're looking! Stop looking! Turn your head, you b-!' (Sometimes Gef is very vulgar.) When asked for an explanation, he said: 'I cannot stand your eyes!' But the animal appears very fond of the farmer and sometimes wheedles him into giving him food, unknown to Mrs. Irving. Occasionally, when his host retires to bed first, Gef, from somewhere behind the panelling, will ask in a low voice: 'Hey, Jim, what about some grubbo?' If no notice is taken, the animal gives a terrific thump on the boards. When given a few biscuits he will talk with his mouth full, and throw crumbs at Voirrey in bed in the next room. Throwing small objects at people (especially 'doubters') is a favourite diversion with this very intelligent mongoose.

I think we have remarked that Gef is clever with his hands, or rather paws. Also, he knows a few tricks. One of these is to tell whether a penny is head or tail uppermost when placed in the deep recess which forms the small window of the porch. Some visitor (a 'doubter' for preference) is invited to place a penny in the recess and return to the living-room. From a squint-hole in the roof of the porch,' Gef squeaks out whether it is a head or a tail. Sometimes he is right. Another sleight-of-paw trick which the mongoose has acquired is to lock persons in Voirrey's bedroom. The room has a latch which -it is alleged-can be operated only from the outside. Both Mr. Irving and Voirrey have been locked in, and Captain Macdonald was the victim of a similar joke during his second visit to 'Cashen's Gap' in May 1935. But an even more remarkable trick was performed by Gef in July 1934. There was some sort of 'tiff' between Mrs. Irving and the animal, who, as a peace-offering, went hunting for a rabbit to give to his hostess. He was determined to be friendly again and said: 'If Mam will speak to me, I will sing two songs for her', and that he had a little present for her. The gift was two biscuits, taken out of a packet in a locked cupboard, which he threw at Mrs. Irving as she lay in bed that same night. Mrs. Irving was not appeased, and the animal remained in her bad books. A few days later, when the farmer was again in bed, and his wife had not yet joined him, Gef shouted out something. Mrs. Irving heard him, and called up the staircase: 'Don't answer him.' Gef then said in a faint whisper: 'Hey, Jim, what about some grubbo? I'm hungry!' This touching appeal to the farmer was too much for him, so he called out to his wife to bring the animal a couple of biscuits. She did so and threw them on top of Gef's 'sanctum' (see Plate IV), the top of the

boxed-in staircase which is in Voirrey's room. Voirrey was in bed, and the room was in darkness. For some minutes they could hear Gef groping for the biscuits with his bony fingers. In a plaintive voice the animal said he could not find them (though at other times he can, apparently, see in Stygian darkness). Mrs. Irving said: 'Shall I give you a match?' He said: 'Yes, pass them to me.' To do this she had to stand on Voirrey's bed. She did so, and Gef took the box out of her hand. He opened it, extracted a match, lit it, said he had found the biscuits, blew the match out, and threw the box into the room. Then he burst out laughing. A few moments later he could be heard munching the biscuits.

Although the Irvings had had Gef literally under their roof for nearly three years, they had by no means sounded the depths of his capabilities. He was always springing surprises on them. Though they knew he could do a little in the way of foreign languages, they were not prepared for the linguistic treat that was in store for them on the evening of July 26th 1934- In succession, Gef sang three verses of 'Ellan Vannin,' the Manx National Anthem, 'in a clear and highpitched voice'; then two verses in Spanish, followed by one verse in Welsh; then a prayer in pure Hebrew (not Yiddish) ; finishing up with a long peroration in Flemish. This is not bad going for a creature that knows so little of his own native language.

In addition to his linguistic abilities Gef is something of an arithmetician. One evening he told Irving that Voirrey had been on the Peel bus seven times in a fortnight, the fare being threepence per ride. 'Seven threes are twentyone, and twenty-one pence are one and ninepence.' Then Mrs. Irving suggested that he should be tried with other sums. 'How many shillings are a hundred and eighty pence?' said Irving. 'Fifteen,' said the mongoose, with only a second's hesitation. Then: 'How many pence in seventeen and sixpence?' In a few seconds Gef answered: 'Two hundred and ten pence.' The farmer remarked that the animal was a long time calculating. Gef replied: 'My rectophone wasn't working!' Mr. Irving put to him a question that he thought would not be answered: 'How many pence in a guinea?' Gef instantly replied: 'Two hundred and fifty-two.'

So far the reader has seen only one side of Gef's nature, that of a clever, mischievous, affectionate, and rather wayward little mongoose. But there is another side to his character, and a less pleasant one. In fact, if he pleases, he can be decidedly objectionable. For example, on one occasion he became so violent in his language towards Voirrey that her bed was moved into her parents' room in case the animal should do her an injury. This was in December 1931, a few months after Gef took up his abode in the farm-house. Voirrey returned to her own room in May 1932. The mongoose was then thought to be a malevolent spirit in animal form. A few weeks before this incident (November 1930, when the father and daughter had retired to rest in their respective rooms (Mrs. Irving was away from home) they both heard a diabolical scream from behind the panelling. Voirrey called to her father to know if he had heard it. He replied that he had put some rat-poison on top of the 'sanctum', and that the animal must have consumed some of it. The screaming continued for more than twenty minutes without ceasing, and then stopped. Mr. Irving said the screaming was as loud as or louder than any human being could make, and reminded him of a pig having its nose 'ringed'. He was so sure that the animal was dead that some of the panelling in the ceiling was removed and Voirrey was sent into the roof to explore. Nothing was found, and the animal appeared quite all right soon afterwards. On another occasion, when the three Irvings were in bed, loud sighs and moans were heard for more than thirty minutes: they were as if a person was in extreme agony. When asked why he made such a noise, Gef replied: 'I did it for devilment!'

During the first few months of his sojourn at Doarlish Cashen, the Irvings more than once seriously considered vacating the place because the animal was so objectionable. That did not cause Gef to mend his ways. His answer to such threats was always: 'I am a ghost in the form of a weasel, and I will haunt you!' Eventually the mongoose became better behaved and more affectionate, and is now terrified if Irving mentions anything about their leaving the farm.

By the end of 1934 the Irvings had come to the conclusion that there was some nexus between Voirrey and the mongoose; a sort of mutual affection which made the animal contented with his life at the farm. They also formed the theory that, in some way, Gef's ability to speak at all was due to some power which he drew from the girl, or which she externalized. But, very curiously, Gef seldom speaks to the girl when she is by herself: usually, one of her parents is with her. The part that Voirrey is alleged to play is a familiar one to students of psychical research, and can be paralleled in nearly every poltergeist case. As a matter of fact, it has been asserted that Gef is a poltergeist in animal form, and that Voirrey is a medium. Some colour is lent to this story by the fact that the manifestations commenced just about the time that the girl reached the age of puberty, and has continued during adolescence. For the story to end in the traditional manner, the 'phenomena' should cease, or shortly cease, as Voirrey is now a young woman. Such mediums as Eleanore Zugun, the Schneider boys, Stella C., etc., lost their powersreal or alleged-when fully developed. When the authors of this work visited Doarlish Cashen in July 1935, there appeared to be little affection between Voirrey and the animal. She denied that she was particularly interested in Gef, and remarked that she would be glad if he left the house. 'He is a nuisance,' she said.

Though Voirrey states that she has no great love for Gef, she has seen more of the animal than any other person. She has seen him many times, and has even photographed him (see Plate VIII). Also, she has seen all of him. On the other hand, her parents have often pleaded with the animal to show himself fully, and have always been refused. They sometimes see a portion of him sitting on a beam, or glimpse something flashing past a gap in the hedge, and that is about all. When they ask him to come into the open, they are met with some such excuse as: 'I am a freak. I have hands and I have feet, and if you saw me you'd faint, you'd be petrified, mummified, turned into stone, or a pillar of salt!' Gef must have attended Sunday school somewhere!

Gef talks most when the Irving family is in bed, and the lights are extinguished. It has been stated that his 'sanctum' is in Voirrey's room, and from this 'rostrum' he shouts out the events of the day: what he has been doing, and what others have been doing. This small-talk is not always acceptable to Mr. and Mrs. Irving, and it keeps Voirrey awake. On one occasion he started screaming out at I I p.m. and talked incessantly until 3 a.m. No one could sleep, and Irving told him to go. Gef replied: 'I am not going to do what you wish. I can stay till 5 if I like!' However, the animal took compassion on them, and in five minutes squeaked out 'Vanished!'his signal that he is about to depart. They heard him jump from the 'sanctum' to the floor. Sometimes, when he is tired, he gives a yawn that can be heard all over the house.

Gef's attitude to strangers is one of frightened aloofness. Very occasionally he will speak sensibly to them. But usually he refuses to speak at all, but throws pins or stones at them, and sometimes spits through a crack in the panelling. When they have departed he makes fun of them, calls them 'doubters' (or something worse) and criticizes their personal appearance. On the rare occasions when he speaks to Irving's visitors he is often rude. In November 1934 a South African spiritualist and her friend visited the farm.

Mr. Irving and Voirrey were away from home. When they returned Gef was persuaded to say a few words and do the 'penny trick'. Then he was asked to step into the room (he was behind the panelling somewhere). His answer to this invitation was: 'No damned fear; you'll put me in a bottle!' When Gef heard that the lady was going back to South Africa, he cried: 'Tell her I hope the propeller drops off!'

Soon after Gef's rudeness to the spiritualist, Mr. Irving was awakened one night by, apparently, some one with a bad fit of coughing. He called out to his daughter to know if it were she who had awakened him. But Voirrey was fast asleep. Then a plaintive little voice came from the 'sanctum': 'It was me coughing, Jim.' Irving asked Gef if he would like a peppermint. The mongoose said 'Yes', so a couple were thrown up to him and he could be heard groping for them in the dark. In a few moments he called out that he had found them. Mr. Irving informed the writers that Gef's coughing was 'absolutely human'. Gef can be nice enough when he is ill, but the mood does not last. Sometimes gratitude gives place to rudeness. For example, not long after the last incident, Mrs. Irving became possessed of an old Bible. One night her husband was examining this book when Gef (who must have had his eye to a squint-hole) shouted out: 'Hey, Maggie, look at the pious old atheist reading the Bible, and he'll be swearing in a minute!' On another occasion he called Mr. Irving a 'heathen' and 'infidel'. Then, feeling angered at something that Mrs. Irving had said, the animal shouted from his sanctum: 'Nuts! Put a sock in it! Chew coke!' This particular bit of rudeness was while the Irvings were in bed. Because no one took any notice of him, he dropped behind the panelling at the head of their bed and gave a terrific thump on the woodwork that shook the place. Two heavy blows followed, but these were in other parts of the house. Mr. Irving told us that the three blows were given in a fraction of a second. Immediately after a box of matches was thrown on their bed. Then the fit of temper passed, and to make amends, Gef asked permission to sing two verses of 'The Isle of Capri'. This was followed by another song, 'Home on the Range'. Then a parody on the same song, which he had picked up from the men at the bus depot. This was really too much for Mrs. Irving, who called out: 'You know, Gef, you are no animal!' To which the 'mongoose' replied, 'Of course I am not! I am the Holy Ghost!' The next morning he drew the outline of his 'hand' in lead pencil on a sheet of paper. Incidentally, he took the paper from a sideboard cupboard in the living-room, and the pencil out of a drawer. He used the kitchen, table as a drawing-board.

The Irvings have often discussed leaving Doarlish Cashen for some more congenial locality. Whenever Gef hears these conversations he says in a pathetic voice: 'Would you go away and leave me?'

Mrs. Irving: 'Yes, you have not helped us.' Gef: 'I got rabbits for you.'

Mrs. Irving: 'You promised to help us to make money, and you have not done so.'

Gef: 'No. If you make money, you'll go away and leave me.'

Of course Mrs. Irving was joking, but Gef pretends to be deeply concerned when there is any talk of leaving the place. Perhaps this is because of the good living which he receives under the Irvings' hospitable roof. He closely scrutinizes the groceries which are brought in, and once he said to Mrs. Irving: 'I know a secret!' Asked what it was, he spelt out 'A-p-r-o-c-o-t-s' -in reference to a tin of apricots which had just been purchased, and which had been put in a cupboard. Only Mrs. Irving-and Gef-knew they were there.

About this period (February 1935) Captain Macdonald was making inquiries as to whether he should pay a second visit to Doarlish Cashen. Gef was implored to promise to reveal himself if the Captain should decide to come. But the mongoose would not promise anything, and, in a burst of temper, exclaimed: 'I'll go to his house and smash the windows with my fist, and those I cannot reach with my hands I'll break with a picture-pole!' To Mr. Irving's question as to what was a 'picture-pole', Gef retorted: 'You know damned well what it is!' He added that the farmer could 'write and tell Captain Macdonald I said so and I'll go and haunt him'. Mr. Irving said the animal could depart and that the family would be well rid of him-a remark which drew forth a plaintive: 'I'm not friends with you, Jim!' A few nights later he volunteered the information that he had 'three attractions'. He said: 'I follow Voirrey; Mam gives me food; and Jim answers my questions.' The Irvings state that that correctly sums up the situation.

When Gef is in a good mood he sometimes plays tricks on the Irvings. About the middle of February 1935, just as the family had gone to bed, he found an electric torch on top of a bookcase. He seized it, jumped up to his 'sanctum' (a distance of three and a half feet) and amused himself by flashing the light on to the Irvings as they lay in bed, switching it on and off, and laughing heartily. To direct the rays from the 'sanctum' (which is in Voirrey's room) it was necessary for him to shine the light through an aperture in the wall eight feet from the floor. Asked how he procured the lamp, he replied: 'Ah! That's magic!' Two nights later he could not find his biscuits on top of the 'sanctum', so Irving told him to fetch the torch and hunt for them. This he did, and switched the light on and off in high glee, finally exclaiming (with his mouth full) : 'I've got the biscuits.' About this period the Irvings thought that Gef must be able to ventriloquize, or that he could speak in one part of the house while his body was somewhere else. As an example of this, the farmer relates a story of how he and his daughter were in the living-room, with Gef speaking just over their heads, telling them exactly what was happening to Mrs. Irving in another room, twenty-five feet away. It has also been put on record by Mr. Irving that Gef can, apparently, transform himself into a cat. Soon after Gef attached himself to the family, the farmer saw a large stray cat, striped like a tiger, outside the house, It was a tailless Manx cat. Mr. Irving fetched his gun and followed the cat, which crossed the yard and turned the corner of a sod hedge into a field. When Irving reached the hedge the cat had vanished. There were neither bushes nor stones behind which the animal could have hidden, and the field was quite flat. When Mr. Irving was relating the incident to his wife that same evening, Gef squeaked out: 'It was me you saw, Jim!' Upon another occasion Gef took a cigarette from a bedroom and, a little later, threw it over a hedge at Irving.

In March 1935 the authors of this work received their first 'gift' from Gef. At the request of Mrs. Irving, the animal pulled some fur off his back, some off his tail, and a few dark hairs from the end of his tail. This was done during the night, and Gef placed the 'exhibits' in a bowl in the living-room. Then the mongoose called out: 'Look in the ornament on the mantelshelf and you will see something frail.' Mrs. Irving looked, and found the fur. This was sent to Captain Macdonald, who asked Mr. Price to identify it. Mr. Price sent the hair to Professor Julian Huxley, who handed it to Mr. F. Martin Duncan, F.Z.S., the authority on hair and fur, for identification.

At last we had concrete evidence as to the existence of some animal whose coat was composed of varying shades of brown and black fur, some fine, some coarse. Mr. Martin Duncan went to a great deal of trouble and spent much time in identifying the specimens handed to him. In a letter (April 23rd 1935) to Mr. Price he says:

I have carefully examined them microscopically and compared them with hairs of known origin in my collection. As a result, I can very definitely state that the specimen hairs never grew upon a mongoose, nor are they those of a rat, rabbit, hare, squirrel, or other rodent, or from a sheep, goat, or cow.

I am inclined to think that these hairs have probably been taken from a longish-haired dog or dogs-the sample contains hairs of two different thicknesses, though this may only represent upper and under coat. Domestic dogs are not well represented in my collection of furs, which is composed chiefly from material we have in the Zoological Society's gardens; therefore, I feel only disposed to suggest rather than make a definite decision, as I have had to base my opinion upon a comparison of the hairs of the wolf and of a collie dog. I did find, however, that both these, in the shape and pattern of the cuticular scales and medulla of your specimens, sufficiently close to make me think that very probably yours are of canine origin.

One point that might be of interest, though trivial at first sight: I could not detect in the hand a single hair showing the root-bulb, which rather points to their having been cut off their animal owner. . . . When you visit the farm, keep a look-out for any dog or other domestic animal about the place with a slightly curly hair and of the fawn and dark colour of your sample; and if opportunity occurs that you can gather a few hairs, it might be worth doing.

A few days later (June 3rd 1935) Mr. Martin Duncan again wrote Mr. Price. He said:

I have now much pleasure in sending you photomicrographs of your 'talking mongoose' hairs, and of hairs from a Golden Cocker Spaniel and a Red Setter. All photographed at x 350 by my special method for demonstrating the cuticular scales. If you will look at these carefully, I think you will agree that there is little doubt that the 'talking mongoose' hairs originated on the body of a dog. (See Plate VII.)

How correct Mr. Martin Duncan was in his opinion will be seen as this story develops.

In the spring of 1935, serious attempts were made to photograph Gef-usually by Voirrey. After refusing to 'pose' for several days, he finally gave his consent (April 6th 1935) and promised to show himself in the haggart (stackyard). He was asked where Voirrey was to stand. He answered: 'How the devil do I know? On the top of her head, if she likes!' in a very surly manner. The morning for the photograph arrived, but Gef disappeared for some hours. He returned the same evening, asked for biscuits, refused to eat them (because they were of the 'afternoon tea' variety), saying: 'You can keep them. I don't like them.' Then the mongoose disappeared for some days, returned, and again promised to sit for his photograph on Sunday, April 14th. He promised to sit on the haggart wall 'with his tail curled up, over his back'. Sunday was fine and Voirrey kept her appointment with the mongoose. But instead of posing for her, he ran along the top of the wall at great speed with his tail in a straight line with his body. Voirrey pressed the button, but, being unused to the camera, did not snap him. As Gef jumped off the wall, he called out: 'I'm not coming out again!' This was the first time that any one had seen Gef so closely or so fully, and Voirrey was asked what he looked like, especially as regards size. She stated that he was rather less than an ordinary ferret, and that the speed at which he ran was 'terrific'. A further attempt was made on. May Day (because Gef was in a congenial mood), when Voirrey persuaded the animal to sit on all fours with his tail over his back, in which position he was snapped. But all these efforts to secure Gef's portrait were futile, as nothing whatever appeared on the film when developed.

Gef has a good memory and he informed his hosts that he was born 'in India'. But he refuses to speak much about his early life; the few details the Irvings have gleaned are either contradictory or false. It was his eighty-third birthday on June 7th 1935, but nothing appears to have been done in the way of celebrating it.

Early in May 1935 Gef pulled some more fur out of his back, and from the tip of his tail. Mr. Irving was away, and his wife had been worrying the mongoose for some more specimens. The animal said he would oblige her, if certain questions were answered. Mrs. Irving promised to do this and, later, Gef called out that there was a 'present' in a bowl on the kitchen shelf. He said: 'It is very precious.' Upon looking into the bowl Mrs. Irving found the fur. Two days later he placed more fur and hair in the bowl, and his contribution included a long, thickish, black hair. Gef said he pulled it out of his eyebrow, and: 'Oh, God! it did hurt!' All the new specimens of fur, etc., were sent to Mr. Martin Duncan for identification. His report was that they came from a dog. He said: 'The so-called eyebrow is obviously one of the vibrisae,' i.e. the coarse hairs to be found about the mouth of mammals (e.g. the 'whiskers' of a cat or dog).

Gef is loyal. On Jubilee Day (May 6th 1935), at breakfast, he informed the family that he was going to Rushen (ten miles away) to celebrate. He promised to let them know what transpired, and the songs that were sung. When he returned he was in a very jovial mood and gave the Irvings a detailed account of the festivities. He said that there were four men there broadcasting, and gave the names of three of them. The account in the local Press confirmed Gef's story. The animal must have been very much behind the scenes as he gave the private conversation between the broadcasters, such as: 'Shall we put on Handel's "Largo"?' and 'You've dropped your fountainpen', 'The current won't last out till 9.30.' These remarks, apparently, were not confirmed. It would be interesting to know why the 'current would not last out'. It rather suggests that the broadcasters were using batteries of some sort.

The reader is now acquainted with the doings, sayings, and history of the 'talking mongoose' down to the period of the middle of May 1935o The record has been compiled from what Mr. Irving told the present writers (during their visit to Doarlish Cashen in July-August 1935), and from what Captain Macdonald related to Mr. Price during the three years that he (the Captain) was receiving letters from the Isle of Man. Mr. Irving's narrative, oft repeated to the authors (who took copious notes), tallies with what he put in his letters.

The letters which Captain Macdonald received from Doarlish Cashen prompted him to make another (his second) visit to the island. The accounts of the diverse-and diverting'miracles' which were of daily occurrence in the farmstead were so intriguing that the Captain thought he might be lucky enough to witness some of the wonders which his correspondent had recorded from day to day. Accordingly, he wrote Mr. Irving to the effect that he would visit the family on May loth 1935. He asked Mr. Irving to impress upon Gef the necessity of showing himself during his visit. The Captain pointed out that it would be too bad if his journey of several hundred miles were to be wasted. And he emphasized that it was important that an independent witness should be available in order to support the evidence of the Irving family.

Gef was informed of the impending visit of Captain Macdonald, and he appeared pleased. He became very lively and talkative, a fact which prompted Mrs. Irving to remark: 'I wish you would talk like that to Captain Macdonald when he comes.' Gef retorted: 'He's damned well not going to get to know my inferior complex!'-a remark which rather suggests that the mongoose did not know the meaning of the words he was using. Mrs. Irving replied: 'You ought to feel honoured that Captain Macdonald will take the trouble to come all this way to hear you, and especially as he is the only one who believes in you and understands what you actually are.' Gef then remarked: 'I might tell him some of my history, but I will not tell him all.' He then sang one verse of 'Ellan Vannin', which, we are told, was rendered in a 'voice that was extremely high-pitched, the tone sweet and clear, quite above the human range'.

Captain Macdonald duly arrived at the farm on May loth, and left on May 23rd 1935. He did not make a report of what took place during his visit, but Mr. Irving prepared one and sent it to the Captain, who passed it on to Mr. Price. The fact that Mr. Irving wrote this report makes it of little value as independent evidence. However hard the farmer tried to make the account impartial and accurate, the fact remains that it is an ex parte report written by the chief supporter of the 'mongoose'. But it was accepted in good faith by the Captain, who assured the writers that Irving's account is an accurate version of what took place. It may be accurate, but it is a thousand pities that the alleged incidents were not recorded at the time, and on the spot, by the Captain himself.

Captain Macdonald arrived at Cashen's Gap at about 7 p.m. on Monday, May loth 1g35Tea was served immediately after, and of course the conversation was of Gef, who had not been heard since morning. Quoting from Irving's report (dated May 24th) to Captain Macdonald: 'As the evening was getting on, it was necessary for Voirrey to leave the house to feed two or

three sitting hens in the stackyard, go to i oo feet away.' When the girl was out of the house, those in the living-room heard Gef scream and say something, which was incoherent. Voirrey returned soon after and asked them whether they had heard Gef scream out the one word 'Sapphire!' Irving continues: 'This use of the word puzzled us, until, without speaking, you lifted your hand off the table and showed a ring on your finger. You then took the ring off, and allowed us to see it, and I then saw it was a sapphire.'

There is something comic about this sapphire incident. The most casual observer, when meeting Captain Macdonald, cannot help noticing that he wears a ring in which is set a large sapphire. The Captain had visited the farm on a previous occasion, and the ring must have been noticed then, as it certainly was during his second visit. That same night, after Captain Macdonald had gone, Gef was asked how he knew he was wearing a ring. He said: 'I saw the ring.' Questioned as to how he knew the stone was a sapphire, he replied: 'Never mind how I know, I know!'

At this point of the report Captain Macdonald adds a note to the effect that, wishing to leave the house after Voirrey had gone into the stackyard (before Gef screamed) he found the door locked: 'The Irvings said: "That's Gef,"' but there was no proof that Voirrey herself did not lock the door behind her when she went out. The Captain had to wait until the girl returned and unfastened the door, before he could leave the house.

When Voirrey rejoined them in the livingroom, it was stated that Gef would do the coin trick for the Captain. It did not transpire how this was arranged: whether Gef promised beforehand that he would do it at a certain time. All the report tells us is that 'After this came the demonstration of the coins (head or tail)'. Captain Macdonald went into the porch and Irving asked him to place a penny in a certain position on the deep ledge of the window. Irving says in his report: 'You went into the porch, and I showed you where to place a penny, and you were to satisfy yourself that we three (self, wife, and Voirrey) were so placed in our livingroom that it would be an absolute impossibility for any of us to see the coin.' This sounds remarkably like a conjuring trick, and it is worth noting that, for the first time during any visit by Captain Macdonald, the entire Irving family was in view while the alleged manifestation by Gef took place.

Captain Macdonald placed a penny in the porch and, it is presumed, returned to the room with Irving, though the report is silent on this point. 'The first time Gef named the coin wrongly.' We are not told how, or from where, Gef spoke. Then the Captain returned to the porch and Gef called out: 'Hanky panky work, he has not touched the coin!' This was correct, but of course, Gef-or whoever called outcould hear that the coin was not moved or tossed. The Captain then tossed the coin again, and Gef called out correctly. The sum total of this 'trick' was that Gef, in two calls, was right once and wrong once-exactly what chance would account for. The interesting part of this story is, that if Irving, his wife, and Voirrey were in the presence of Captain Macdonald when Gef made the calls, where did the 'voice' come from? The room is dark, whether by day- or lamplight, but not so dark but that ventriloquism could have accounted for the voice. We are not told the exact positions of each member of the Irving family, where Captain Macdonald sat, and where the 'voice' came from. But there is no evidence whatever that the owner of the 'voice' saw the coins: the calls were sheer guesswork.

During the next day (May 2 i st) Captain Macdonald and Mr. Irving walked about the village of Glen Maye, and had lunch at the Waterfall Hotel. Upon their return to the farm Mrs. Irving at once told the Captain what their conversation at Glen Maye had been about, and what Irving had had to drink for lunch. She stated that Gef had been present, unseen, during the meal, and had followed them about. The animal reached the farm before her husband and the Captain, and had given Mrs. Irving an account of some of their doings. Without suggesting that anything of the sort took place, it is obvious that collusion between Mr. and Mrs. Irving could have accounted for the seeming miracle.

Later, when Voirrey was again in the stackyard 'feeding the hens', Captain Macdonald and Mr. and Mrs. Irving heard Gef call out: 'Plus fours. Oxford bags', an allusion to the way that the Captain was dressed. Mr. Irving continues his report to Captain Macdonald:

When he [Gef] said these words, the voice was a few feet away, and behind the wainscot, my wife and self were both within a few feet from you, and in full view also, and Voirrey at this moment (and this is important) was 100 feet away from the house, out of sight and out of sound in the stackyard, and I at once asked you to come to the window and see for yourself, and in 2 or 3 seconds, she appeared at the entrance to the stackyard, coming towards the house.

Of course, there is no proof whatever that Voirrey was a hundred feet away when the 'voice' manifested. All that the Captain saw was the girl returning from somewhere, after the voice had manifested. There is no evidence as to where the girl was when the voice was speaking. It is a pity that Gef again waited until the girl left the house before he spoke.

It was midnight when Captain Macdonald left the farm-house. Mr. Irving accompanied his guest to the hotel. Mrs. Irving and Voirrey remained in the house. The night was quite dark. When the Captain and his host were eighty paces from the house 'Gef called out "Coo-ee!" to us'. The animal afterwards admitted that it was he calling out, ten feet from where the two men were walking. But again there is no proof that either Mrs. Irving or Voirrey were where they were supposed to be, viz. in the farm-house. Mr. Irving concludes his report to Captain Macdonald in the following words:

Now what I wish to impress upon you is this: in these two experiences, you have had what no one else has had (excepting ourselves), that is, you heard him speak in the house whilst my daughter was out of the house (100 feet away), and he spoke to us both, outside the house and when my daughter was in the house.

Unfortunately, there is no real evidence that Voirrey was not out of the house when she was supposed to be in; or in the house when she was supposed to be out. It was a pity that Captain Macdonald did not prepare the report himself.

|

|

||

| |

||

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received

The Editor HTML Transcription © F.Coakley , 2010 |

||